Kherson: A critical battle

The planned Ukrainian counteroffensive in Kherson will determine whether Russia marches up the Dnieper on both banks, as well as Russia’s ability to compel Ukraine to surrender Odessa.

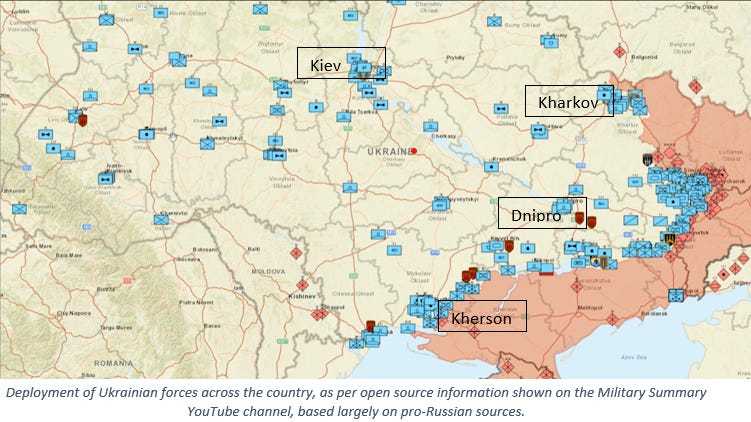

Ukraine is engaged in a counteroffensive in the Kherson region in southern Ukraine. The area is mostly flat and agricultural – meaning that there is no natural cover against artillery or aerial attacks. Furthermore, Russian artillery in this region fires six shells to every shell fired by Ukraine. Despite that, Ukraine is targeting three major bridges connecting Kherson and its environs to the east of Ukraine. These are the bridge over the Khakovska dam, across the Dnieper River, the Antonovksy bridge, which has been damaged and also traverses the Dnieper, and the Darkiyvka bridge between Kherson and Nova Kakhovka. The objective appears to be to cut off or at least complicate Russian resupply to the Kherson region It is worth noting that there is a small risk that the artillery and rocket attacks would destroy the Khakovska dam, causing a humanitarian disaster, though destroying dams is notoriously difficult. Furthermore, the Ukrainian units in Kherson are not operating at full strength, as some have had battalions deployed to Donbass, according to pro-Russian open source information. That said, in recent days, there have been reports that some units are redeploying from Donbass back to Kherson, making an accurate assessment very difficult.

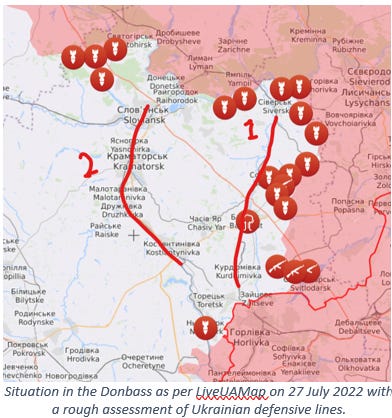

Donbass

Meanwhile, the battle for the Donbass is ongoing. In addition to beginning to breakthrough outside the city of Donetsk, Russia is pushing towards the Ukrainian defence line running from Siversk to Soledar to Bakhmut to Kurdiumivka. The next Ukrainian line runs from Sloviansk to Kramatorsk to Kostiantynivka. Should Russia break through these two lines, its path would be clear all the way to Dnipropetrovsk, also known as Dnipro, on the Dnieper River, where the Ukrainians have concentrated some reserve forces. The Donbass has the highest concentration of Russian and Ukrainian forces, and the Russians are close to a breakthrough there. Crucially, the region is also where the best and most experienced Ukrainian forces are concentrated. The defeat of these forces would very much limit Ukraine’s military options. Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) DPR officials have set themselves a deadline for the end of August for this to be achieved.

Kherson’s importance

The reasoning behind the counteroffensive in Kherson appears to be to isolate the Russian forces in Kherson with a view to regaining that region, while the attempted destruction of the bridges suggests that Ukraine is not expecting to regain territory further east – including Crimea. For Ukraine, capturing Kherson would fulfil at least three objectives:

Firstly, it would allow Ukraine to release some of the forces concentrated in Nikolayev and Odessa and use them in future defensive and offensive operations.

Secondly, it would allow Ukrainian forces to establish a defensive line behind the Dnieper River without the threat of Russian forces flanking them from the south. With Kherson in their hands, the Ukrainians would be in a better position for the winter of 2022 - 2023 and would be in a better position to negotiate terms with Russia. Should Russian forces remain in Kherson, however, they would be able to move up both banks of the Dnieper River after the battle of the Donbass is done, making future battles much harder for Ukraine. Russia would also have the option in late 2022 to move west from Kherson towards Transnistria, effectively cutting off Odessa and the Black Sea coast from resupply by Ukraine and bottling up the units in Odessa. Russia could then negotiate terms under which Odessa would simply be surrendered.

Thirdly, capturing Kherson, or at least launching an offensive there, would prevent Russia from organising a referendum for Kherson to unify with Russia. Such a referendum would represent a major media victory for Russia, and, if coming on the heels of a Ukrainian defeat on the Donbass, would reduce the appetite of Western publics for the Ukraine war and for the cost of sanctions.

Outlook

That said, my view is that it is highly unlikely that a Kherson counteroffensive would succeed. Destroying bridges is extremely difficult, and, while the bridges have been damaged, the Russians have shown that they can repair them in quick order and increase the availability of air defence systems. In addition, the Ukrainians lack adequate offensive air support as well as natural cover, making them highly vulnerable to Russian artillery when they attempt any advance. Furthermore, the time that the Ukrainians have for a counteroffensive is limited. The battle of the Donbass is nearing its end and may well end by September, allowing an experienced and skilled Russian force to launch offensives in multiple directions, as well as allowing Russia to reinforce Kherson. The objective of the counteroffensive may well be to simply slow down Russia in the hope that Russian forces would have to spend winter in an unfavourable position, while Ukraine is rearmed by the West. On the other hand, should Russia defeat the Ukrainians decisively in the Donbass and in Kherson before September, then Ukraine would find itself in a very difficult position, with winter making the digging of new defensive positions much harder in Ukraine’s north, while the south remains vulnerable for a longer period to attacks by Russia. Ukraine would not have enough left to maintain the fight, and Russian advances could accelerate significantly. This would make it more likely that Ukraine would accept peace terms imposed by Russia.